Substack's Algorithm Doesn't Get Me

And that's OK. All these "gentle musings," invitations to "grow," and inspirational Instagram copypastas are doing wonders for my doomscrolling habits.

Every morning on my days off, I sit down in front of my computer screen with a fresh cup of tea and allow myself a brief moment of hope. Perhaps this will be the day when Substack’s algorithm greets me with something other than extreme sentimentalism.

“Allas,” quod Stephanie, “and weylawey.”1

I’m not entirely sure why Substack thinks I want to see saccharine platitudes ripped off some Pinterest influencer’s mood board, BUT OH BOY, does it ever seem to enjoy tossing armloads of the stuff my way. Clicking “hide note” and “show fewer notes like this” is about as effective at containing the onslaught as slapping a 2x2 gauze on a dehisced sternal incision.2

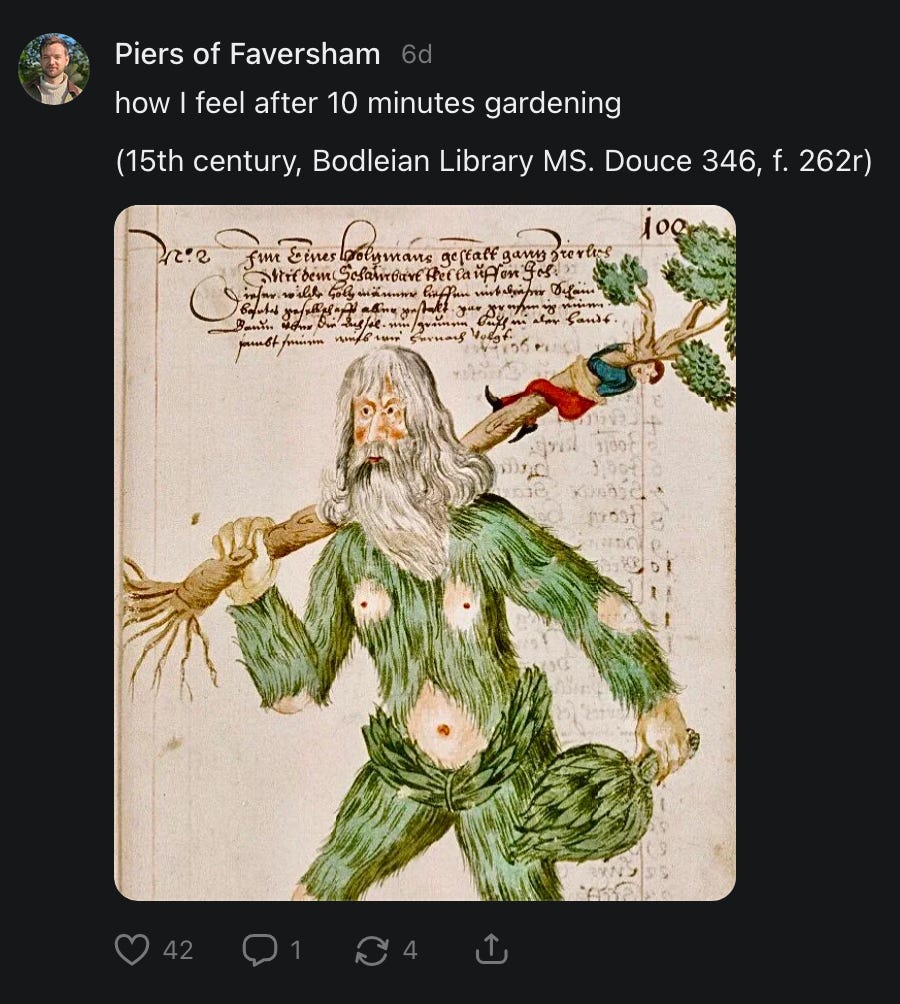

I’m not the only person who has noticed this. In a rare moment of “getting” me, my Substack homepage presented me with this absolute gem:

Now, don’t get me wrong here: all good-natured teasing aside, I absolutely think this stuff has its time and place, and it doesn’t bother me one iota that it’s on Substack. If earnest writing about quiet living is the kind of thing you enjoy producing, have at it! I’m just … not interested in reading it, because it’s not my thing, and I really wish Substack would stop recommending it to me.

To be fair, I’ve only been on Substack for about a week. I haven’t given the algorithm all that much data to work with yet. At this point, it couldn’t possibly understand that I’d be equally tickled to look at 14th century LARPing snails and important TED talks by badass journalists. Substack’s Notes feature is also still rather new itself. Some growing pains of the sort outlined by this user are to be expected.

Even if I allow for this, though, it doesn’t really explain why I’m continuing to see overly sentimental notes on my homepage after going out of my way to mute them. Perhaps I pause just long enough while scrolling for the algorithm to record this as “interest,” when I’m actually screwing up my face and going “what, ANOTHER ONE?”

The only conclusion I can reach is that Substack’s algorithm just isn’t all that great. Not yet, anyway. But maybe that’s a blessing in disguise, considering what I write about in this newsletter.

Bad Algorithms Are … Good?

You don’t need me to point out the now-obvious. “Good” algorithms — the kind that seem to anticipate our thoughts before we have them — predispose people to social media addictions, particularly when paired with bottomless homepages. Much has already been written on this subject,3 so I won’t retread that particular ground.

What I’ll focus on here instead is the way in which less-intuitive algorithms offer a kind of unintentional safeguard from the addictive aspects of social media. An algorithm that doesn’t entirely “get” its users is a lot less likely to feed them the sort of content that keeps them scrolling endlessly. I know I certainly lose all desire for a good scroll sesh when I’m invited more than once to “quietly meditate” on how “reading is a gentle act of rebellion in a hurried world.” Sparkle emoji.

There have been plenty of calls — and a few steps in the right direction — for greater regulation and oversight of addictive social media algorithms. Governor Kathy Hochul (D-NY), for instance, signed New York State Senate Bill S7694A last year, establishing the “Stop Addictive Feeds Exploitation (SAFE) For Kids Act prohibiting the provision of addictive feeds to minors by addictive social media platforms.”

The bill’s authors state the following:

Research shows that spending time on social media is ten times more dangerous than time spent online on non-social media. Self-regulation by social media companies has and will not work, because the addictive feeds are profitable, designed to make users stay on services so that children can see more ads and the companies can collect more data. [emphasis added]

While I agree with this statement, I’m also going to challenge the bold section a bit.

Developing excellent recommendation algorithms is something that all major social media platforms, including Substack, ostensibly work towards. I would posit, however, that a less-perfect, less-addictive algorithm could still help companies achieve their growth goals while also being healthier for users on the whole. My experience on Substack thus far has been a great case in point.

Encouraging Intentional Engagement

Substack’s homepage algorithm hasn’t been a complete disappointment. It has, on the odd occasion, recommended stuff to me that’s right up my alley.

What this has demonstrated to me is that there is stuff I’ll enjoy floating around on this platform — I just have to be a little more active in seeking it out if I want more of it. It feels a bit like the Internet of Yore, where you would occasionally stumble across a site or forum post you liked, but had to make an actual effort the rest of the time to find similar content.

The stuff I don’t want to see, the stuff I keep hiding in apparent vain … it doesn’t keep me from using Substack or engaging with the platform; it just keeps me from scrolling passively through my homepage for hours on end. It encourages me to actively use the category tabs, the leaderboards, even the humble search bar. I’ve discovered some great authors this way, and expect this will only continue.

While findings are inconclusive and more research is needed, the difference between passive and active engagement on social media could have significant implications for mental well-being. Anecdotally, I’d guess I’ve spent almost as much time on Substack over the past week as I recently spent on Reddit while recovering from the flu, but the way I feel about it is completely different. I haven’t spent my time here doomscrolling or starting arguments with bots; I’ve spent it searching for articles I actually want to read (not, you know, gentle musings), conversing with interesting people who have interesting things to say, and above all else, drafting my posts and creating my silly images to accompany them. It feels rather nice.

People are increasingly waking up to the fact that “good” recommendation algorithms are terrible for them. That’s why Substack is riddled with Instagram refugees. That’s why all your friends are gravely announcing their departure from Facebook via … a Facebook status update (cough, I’m not guilty of that at all, cough). “Addictive feeds” are profitable, indeed, but for how much longer? Is the end of social media near, as asks?

Time will tell.

Why Even Have Recommendation Algorithms?

Someone reading this post might ask, “well, if what you’re ultimately proposing here is a half-baked algorithm to encourage greater use of active content discovery features, why even have a recommendation algorithm in the first place?”

It’s a valid question.

Personally, I dislike all-or-nothing propositions as a general rule. I don’t think there is anything inherently wrong with delivering a bit of personalized content to consenting users based on their previous browsing habits. It only becomes a problem when this kind of highly-curated content is all we ever see on a platform, especially when we can scroll through it endlessly and aimlessly.

Recommendation algorithms are good in that they show us enjoyable stuff we might have otherwise overlooked in the vast ocean of user-generated content. They’re also good for social media companies in that they demonstrate tangible value to users — and tangible value can lead to revenue opportunities, which obviously keep platforms like this one alive. Dopamine for all, client and developer alike! But as with most good things that light up the reward centres of our primitive monkey brains, algorithms are undoubtedly best enjoyed in moderation.

So, you know what? Disregard what I’ve said previously about my lack of interest in all those quiet musings on gentle living, Substack. Keep ‘em coming. Give me all of your gentle rebellions, your sparkle emojis, your simple statements presented as profound wisdom. Give me reasons to keep actively seeking out the sort of long-form articles and amusing notes I want to see instead of scrolling passively. It’s better for me. And it’s probably better for you in the long run, too, Substack.

… but do feel free to toss out the occasional manuscript meme when I’m having my morning tea, if you don’t mind. That shit, as the kids say, is fire. 🔥

That was an obscure Chaucer joke. You’re welcome.

That was an obscure medical joke. I’ll be here all day, folks. This is the kind of highbrow comedy you can expect from an English major who went on to work in health care.

If you want a decent primer on it, here’s a recent journal article on the neurophysiological impact of social media algorithms on adolescent brains.

I enjoyed this and you're very much preaching to the converted. Even though I barely know a thing about medical terminology, that paragraph beginning with "I’m not entirely sure why Substack thinks I want to see saccharine platitudes..." and ending with "dehisced sternal incision" cracked me up. That's comedy gold.

And I was delighted to see your rant on 'gentle musings' and its brethren. I've long been a prankster on notes and I've loved calling people out on their excessive use of 'musings' (and its iterations) as well as the endless overearnest banal empty platitudes exhorting us to 'show up' more often and 'be present' and 'never give up' and blah blah blah. In homage to this drivel, I even wrote a book on a daily journalling theme, with a subtitle that included 'musings' in it. I doubt people will pick up on my ironic use of it.

The algorithm has somehow led me to you! So here I am.

I think that once you follow more people, it starts to show you content from them and people they like. But it doesn't explain why, out of the box, you see so many exiles from Insta. But maybe it's a reaction to the stressful stuff that you get on other platforms. That said, when I first looked at Notes, I saw loads of posts from people telling me they'd given up their day jobs to write here and how awesome it is (but then, I suppose it makes sense that they'd surface Notes that make them sound good!).